Ulam Unearthed or Why I Am Writing About a Polish Mathematician

- Chris Rzonca

- Mar 30, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 10, 2025

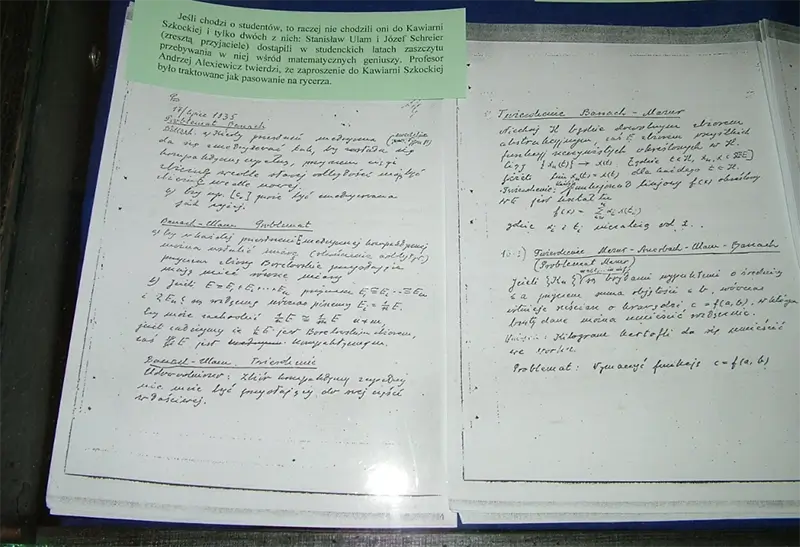

Does the Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam (1907-1987) need to be unearthed? Perhaps not. In the world of advanced mathematics, he has been well-known since his twenties. As a young member of the famous Lwow School of Mathematics (when this multi-ethnic city was part of Poland, now part of Ukraine called Lviv), he published his first of many mathematics papers. His tutors, famous in their own right, were Stefan Banach, Kazimierz Kuratowski, and Hugo Steinhaus. His move to the United States began in 1935 when he was first invited to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton by John von Neumann where he repeatedly spent the academic year, returning to Lwow for the summer. In Lwów, he continued to frequent the Scottish Cafe, a meeting place for mathematics professors and graduate students and visited by an international assortment of mathematicians. It was at this cafe that problems were written on marble table tops before being transcribed into a notebook that came to be called The Scottish Book. This compilation of problems and solutions, containing the work of many mathematicians, survived the war and was later translated into English and published by Ulam himself, serving today as a testament to the vibrant mathematical life of Lwow between the wars.

When Ulam left Poland with his younger brother, Adam, in August 1939 he could not have known that he would never see the rest of his family again. They were murdered by the Nazis along with so many other Jews. Without financial support due to the war, he initially struggled in America but eventually landed a position as a Junior Fellow at Harvard and when that ended, he moved to the University of Wisconsin for a low-level teaching job. From there he was recruited to join the Manhattan Project (the code name for the development of the atomic bomb during World War II) centered at Los Alamos, New Mexico. Led by J. Robert Oppenheimer, physicists, engineers, and other technicians worked feverishly to develop this fearsome weapon because it was believed (falsely, as it turned out) that the Nazis were close to developing such a bomb. At Los Alamos, working, thinking, and discussing ideas alongside other brilliant scientists, he was reminded of his days at the Scottish Cafe in Lwow.

Ulam's work on the complex calculations for a critical part of the design made the bomb a success. After the war ended, a more powerful bomb was proposed but its development was stalled. Ulam once again was called upon to do extensive and tedious calculations proving that the original design by Edward Teller was not feasible. Ulam went further, however, and invented a new design. Despite the fact that two of the three elements of the successful design are Ulam's, Edward Teller unfairly and dishonestly claimed credit, flatly refusing to co-sign the patent application or accept the fact that it was Ulam's ideas that broke the deadlock of his own three years of fruitless work. But of course, Ulam had a role in ensuring his own obscurity. Why didn't he insist on the recognition due to him?

It seems he was simply not very interested in taking credit for any of his work on either bomb. For him, it was the scientists' job to discover new things and that during wartime (including the Cold War) everyone was working together. Neither he nor most of his colleagues could be bothered with petty things like individual recognition. Teller was the exception. He seemed at that time very anxious to advance himself in the world of physics, much more than advancing physics.

Stan Ulam was pretty much the opposite. His ambition was for working on new and exciting problems in physics or mathematics. Once a particular problem was solved or a discovery made, however, he quickly lost interest and moved on to the next thing. He was unconcerned with fame or fortune, so unlike Teller, whose ambition and arrogance knew no bounds. Teller thoroughly enjoyed being called the "Father of Hydrogen Bomb," becoming a celebrity based on a lie. Ulam, on the other hand, followed his own heart and intuition into other areas, like the foundations of computer programming or applying mathematics to biology. Perhaps more tellingly, he never adopted that very American penchant for shameless self-promotion, preferring a humble, almost nonchalant attitude toward his many outstanding accomplishments.

Both men were undoubtedly geniuses and did important work at Los Alamos, but I think Ulam had greater self-confidence and thus little need to promote himself. Teller used the atmosphere of post-World War II America, with its explosion of interest in scientists and their contribution to winning the war and improving national security, to boost his own ego and influence politicians to benefit himself. Ulam found this kind of self-promotion uninteresting and unnecessary. He felt no need to toot his own horn. He would rather leave that to others. In post-war Los Alamos, however, while some colleagues championed his cause, most moved on to universities or other positions and Stan was mostly forgotten.

Some might say that he had only himself to blame for his obscurity, that and the fact that much of his work remains classified to this day. Few people outside of the Los Alamos group know about his contributions to building the atomic bomb and not many more knew about his hydrogen bomb design.

The brief history above may explain why I am writing about Stan Ulam. There is an injustice here. Obviously, his story deserves to be told to the world, whether he wanted it to be or not, whether you support the building of weapons of mass destruction or not. We must remember what was at stake at the time. The Germans were thought to be ahead in building an atomic bomb and later it was feared the Soviets might have be first to build the hydrogen bomb, so it was imperative that the US build them first. Yet the question remains--why didn’t Stan Ulam get the credit he deserved then and why does he remain so obscure today?

There must be many reasons aside from the personalities of the two men. As a Pole, Stan's origin may have worked against him, even though he became a US citizen in 1941. Poland was on the wrong side of the Cold War. But Teller was born in Hungary, a country also behind the Iron Curtain, so that cannot be the reason. Then again, it is not just the Americans who have basically ignored Ulam, the Poles have not had much to say about him and his accomplishments, perhaps because most of his work was done in the US. It's as if he was caught between these two worlds. I don't think we will ever completely understand why his story has not been fully and properly told. I do know that it is time to set the record straight.

"The Scottish Book"

The Building on University Street, where the Scottish Café was located in the 1930s

Kiedy dowiedziałem się o Hiroszimie i zobaczyłem fotografie zniszczeń, pierwszym uczuciem było zdziwienie. Nagle w moim mózgu dokonał się niezwykły skrót myślowy: cyfry, wypisane białą kredą na czarnej tablicy, i natychmiast potem miasto zmiecione z powierzchni ziemi - St. Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam - Polish-Jewish-American mathematician, nuclear physicist and computer scientist. B. April 13, 1909 in Lwów, Austria-Hungary – d. May 13, 1984, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Graduate of the Lvov Polythechnic Institute (1933), worked in Princeton, Harvard, and the University of Wisconsin. In 1943 was recruited to work at Los Alamos National Labrotary and played a major role in the development of the first atomic bomb, used in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and then the hydrogen bomb. Died suddenly of a heart attack; buried in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris on the initiative of his French wife, Françoise Aron. Author of A Collection of Mathematical Problems (1960), Sets, Numbers, and Universes (1974), and Adventures of a Mathematician (1976).

Chris Rzonca teaches writing as part of the Liberal Studies curriculum at New York University. He has written about the Polish writer Andrzej Bobkowski (Polish Review), theatrical performances and other theater-related events in Poland for European Stages (publ. in New York). His photographs were shown in solo exhibitions in Warsaw and Kazimierz Dolny; a new exhibition is forthcoming in August, in France. He is currently working on a film script about the life of Stanislaw Ulam.

Comments